The Friendship Paradox is the phenomenon where our friends, on average, seem to have more friends than we do.

My particular interest in this phenomena came from a curiosity around social comparison and its effects on social well-being as well as friendship specifically and social dynamics in general.

Let’s dig into the paradox a little more:

Why Does This Happen?

In a nutshell, the distribution of friendships in a social network are not normally distributed. Instead, they follow something of a power law where a few people have a high number of friendships and many people have only a few friendships.

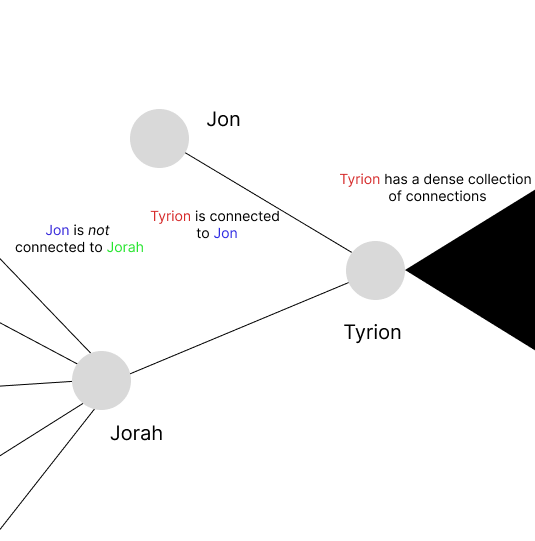

For example, let’s imagine Tyrion, a super-connector with hundreds of friends, and Jorah, who has only five friends.

Now let’s take look at Jon, a third person in the network. It’s more likely that Jon will be friends with Tyrion than with Jorah because Tyrion’s wide circle of friends makes him more likely to be included in others’ friend lists.

In fact, people like Tyrion with many friends are more likely to be named in other people’s friends lists simply because they have more connections. This leads to highly connected individuals like Tyrion being over-represented when friend lists across the network.

Thus, on average, our friends appear to have more friends than we do because the presence of super-connectors skews the average number of friends higher.

Notes on the Data

In order to explore this further, I analysed the Stanford Network Analysis Project (SNAP) Facebook dataset.

The dataset offers social network graphs for a set of anonymised Facebook users.

Here is some social network terminology that readers may be unfamiliar with:

- node: represents a particular user in the social network.

- edge: the connection between two nodes

For example, the example social network between Tyrion, Jorah and Jon above may look like this:

Before jumping into the analysis, here are some things to keep in mind:

- A user’s list of Facebook friends count probably don’t represent their actual friendship status. However, they may provide a useful proxy for assessing the friendship of a particular user (interesting assumption to explore).

- The edge data was represented in a series of separate subnetworks files. The ego / centre node of each network was not explicitly represented. Including these nodes would probably amplify any friendship paradox signal in the data as these are highly connected individuals.

- In addition, in this early pass, the separate ego networks were analysed in isolation. However, later analyses can integrate these networks to see how this may change the results.

What SNAP tells us

To see the Jupyter Notebook used to analyse the data, please visit the corresponding Github Repo.

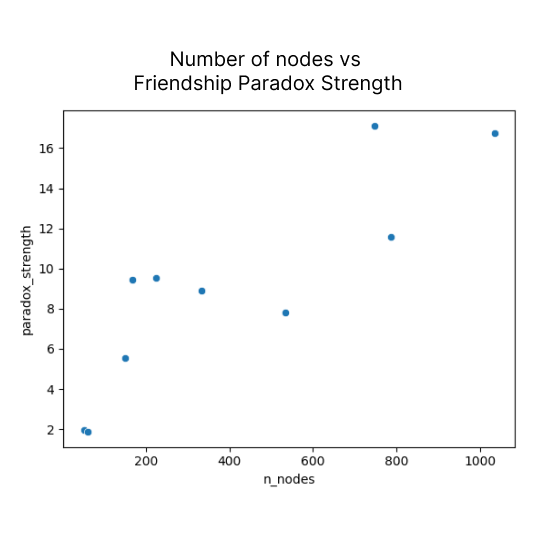

The larger the number of nodes in the network, the more pronounced the friendship paradox.

That is, the larger the network, the larger the discrepancy between an individual’s number of friends and the average number of friends of that individual’s friends.

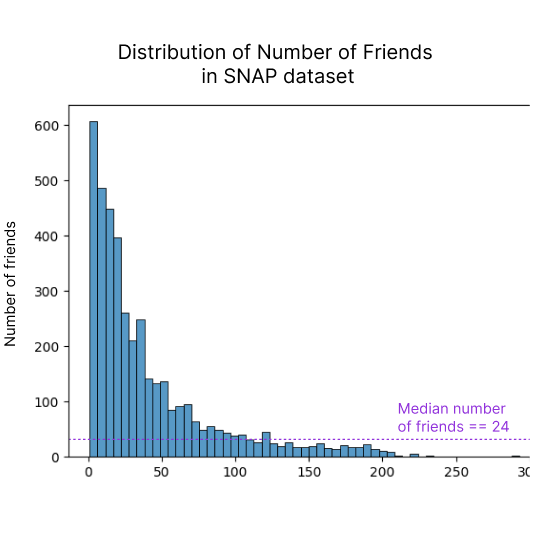

In addition, as expected, the distribution of number of friends follows a power law distribution with a few individuals having a large number of Facebook friends and a large number of individuals having a few Facebook friends.

The median of 24 friends is useful as it is less influenced by the super-connectors with 200+ friends.

What next?

However, is this kind of evaluation common? I can’t remember having consciously thought to myself “Gee, people in my network certainly seem to have more connections than me.” (Though I have written about how such social comparisons can be powerful in influencing our behaviour)

And I’m someone who does a lot of exploration on their own thoughts!

My preliminary search (reading abstracts only) is a bit mixed but largely suggests that people don’t use friends of friends count to understand their own popularity (Bravo et al (2024), Zabala et al (2020)).

An additional caveat to the preliminary nature of the search: both of these studies were conducted on adolescent samples and these assessments may not generalise to adult populations.

This is something I am going to dig deeper on as it feels like some of the consequences of the friendship paradox tend to rest on this assumption.

For the code related to this analysis, you can see my github profile.

If you enjoyed this, you may also enjoy: